This work of fiction was originally published in Broad Knowledge: 35 Women Up To No Good

It was about the time my mother fell in love with the dogman, that I ceased to be human. Daddy was driving during a thunderstorm when their car broke down on the side of the mountain. The dogman stood in the trees soaked in the downpour, carrying a big buck in his arms with his hand around its throat. The buck’s eyes were wide open but almost tranquil, washed to gleam in the headlights. Dogman stroked the buck’s rigid back, as if it were his pet.

When my mother locked eyes with him, he growled. The black fur on his arms and legs stood up, and his body went electric-taut. The buck kicked his legs, and in a single motion the dogman broke its spine.

My mother gasped. She grabbed Daddy's hand to steady herself as the dogman, with long, graceful strides, carried the buck off into the forest.

“I thought I was done for, Effy!" she told me later at the kitchen table, smiling. "He must’ve been ten feet tall, and handsome. You could tell he was handsome, even through all that rain. Those dark haunches, that wide chest."

She grew heady during thunderstorms. She dressed in her silky pink nightgown, the one Daddy gave her six years ago that she never wore for him, and stood out in the trees behind the house. Flashes of lightning illuminated her pale, wide thighs and her wet red hair spilling over her back. She held her hands out, as if he might reach out to take them. She bit her tongue waiting for the dogman, and after the storm passed she came back into the house with blood in her mouth.

If Daddy was troubled by his wife's new crush, he didn't show it. After work he spent most nights upstairs in his office, his "laboratory", reading books about wine-making or tending to his dead spider collection. He'd progressed slowly over the years, from a father into an antique fixture. Something that was part of the house, but not exactly living inside of it.

Once he went down into the kitchen to pour water, and his hands remained steady against the pitcher as my mother slapped me.

For what, I couldn't remember. Maybe I left the stove on. Maybe I was wearing a dress that only a slut would wear. What I did remember, was this: that as I knelt on the floor, my hand trying to cover the lacing of blood now pouring out my nose, he placed the pitcher back into the fridge and walked back upstairs.

I was still human back then, so those things hurt me.

But by the time my mother began to plant flowers for the dogman in our garden and slaughter the chickens so that she could smear the blood in between her menopausal thighs, I didn't feel much at all.

It was my senior year of highschool.

I often skipped class to spend days in the forest. I’d take my brother’s hunting bow, his buck knife. I hunted small things. Squirrels. Hawks. I built myself a hidden shelter out of thick branches and plant rope and I often slept there, not coming back home for days. At night I travelled by star light, baptized myself in cold springwater.

And sometimes, I watched my mother, from the trees, as she babied the Ozarkian crocus, the delicate orchids she could never quite keep alive, the violets that wilted to one side.

I’d only ever seen her be gentle to flowers and wine glasses.

#

Some people think that once you are born human, you will always be human. But it is easy to lose, easier than anyone might think.

In the forest I pretended that I was an animal, that I’d never been born in that homestead house with its corset-tight rooms and dirty linoleum. I was an animal that never crawled on all fours through a dark creaking hallway, picking up the bloodied pieces of a 32 glass dinner set. I was an animal that never had her braid slammed shut into a cupboard, or had a boy shove her skirt up over her mouth, or had her fingers smashed in a car door.

And it worked, for a while. The nights that I slipped through the trees were quiet ones.

But then I started dreaming of the dogman.

Nobody believed in the dogman, not really. He was something to talk about in the hushdark so that your girlfriend would snuggle close, or to delight-frighten children so that they’d yell and squirm. Everyone knew of an uncle, or a grandparent, who’d seen the dogman in a flash of headlights, or leaping over a garden fence. But he wasn’t real.

Before he left town, my brother took me to an old shrine while we were out hunting. It must’ve been over a hundred years old. A white oak, with barbed wire wrapped around its trunk, and the bones of small animals tied to the branches with twine and cord. The air was still.

“People used to come here and pay him tribute. So that he wouldn’t steal their crops, kidnap their daughters. Things like that,” he said. “When it’s windy they make this music. It’s hard to describe. Pretty. I’ve never heard anything like it.”

He pulled one of the bones down, a tiny, weatherworn crow’s skull with the cord looped through its eye sockets, and placed it in my hand.

“Keep this, it’ll protect you from him.”

“You really think that?” I asked.

He reached out to tap a hanging bone necklace, and watch it undulate.

He never answered.

One night as I slept in my little hidden shelter, I dreamed of the dogman. I tried to move, but I couldn’t, my limbs constricted tight by some invisible, thick liquid. He was shuffling around in the dirt outside, snuffing, making these barking pants.

And every time I breathed, in quick stolen gasps, his movements grew more sporadic, more forceful. As if he could sense me, but couldn’t find me, not quite, and my pulse drove him into a frenzy.

And then I could move a finger, two. But I didn’t dare run. He’d catch me and tear me apart. I knew the noise of violence that was only looking for a home, a comfortable place to kill. So I only moved my hand down to my pocket, to grasp the crow skull necklace.

It was one of the few things that I always kept with me, in and out of dreams.

He created a storm by running back and forth. Trees crashed to the ground. Animals squealed, as they were torn apart. I pressed my back into the dirt, trying to force my breathing to slow.

But I was breathing faster and faster, and the storm was picking up. Hurling. Heaving. More trees, collapsing. The sound of a wolf’s throat being torn out mid-howl.

Then, he upended my little shelter, crumbled the sticks in his hands. His great paw reached for me, blotting out the sky. And then—

The dogman disappeared. The night disappeared. I climbed out of the wreckage of my shelter into daylight.

He’d torn up the entire forest. Nothing remained but the grass he’d trampled into ash and the stumps of trees.

My mother, in her pink nightgown, sat cross-legged on what remained of a white oak. Ragged, red claw marks swathed her face and chest.

“Oh, Effy! He was beautiful!” she said, rocking back and forth, grasping her ankles, laughing. “We killed everything. Nothing survived . Tomorrow night, he’s taking me to space. We’re going to destroy a satellite!”

Then I woke into a hazy, gray kind of morning air.

The dream felt real. It was the kind of dream you wake up from and your chest is sore.

And as I walked home I kept looking behind me, through the trees. Feeling him but not feeling him, in the way that a shadow has no weight but seems to drag heavy, despite all natural laws.

I reached in my pocket and touched the crow skull.

#

For the first time in weeks, I combed the bugs and leaves out of my hair, and went to school.

In the hallway, I walked past a parade of people I tried to avoid. Like Mr. Sandalwood, who once squeezed the back of my neck at a football game and told me how fragile I looked, standing there by myself. He did not smell like his name, like sandalwood. He smelled of overripe oranges and too-strong mint mouthwash. Like a dog masking his true scent.

Or the girls with straight-shoulders, backs like hollow trees. Evangeline and Lily and Terra, girls with names like flowers and cathedrals, names that did not flow with blood. It was Evangeline, at her poolside party in her golden bikini, clutching her tiny pink towel, who put her arm around around my shoulder and asked:

“I always see you by yourself. Tell me what boys you like? I can get you any boy I want.”

Me, shrugging. “I don’t know.”

“You don’t know?” Evangeline said, laughing. “Of course you know. Is it Andy? Miles? It’s Miles, isn’t it?”

Evangeline set me up with Miles for a dance.

He broke my wrist when I wouldn’t kiss him in his car.

Afterwards in the hallway between classes, I ran into Evangeline. I held my broken wrist between our bodies like a white flag.

But she only rolled her eyes at the sight of the puffed up, bruised blue bones.

“I told him you wanted him. And just look at you, the way you act. You pretend like you’re invulnerable” she said. “Well, you know. You’re not.”

The human parts of me, that stuck stubborn to my skin, were coming off in flakes.

It’d been easier to hold onto them, when I thought in those early days at home that I’d meet someone kind.

Yet kind people were talked about in the same way the dogman was. Seen in flashes. Sideway glances. A campfire tale. “My great-great grandmother met a kind man once, as she crossed the ocean on the Mayflower. He smiled genuine, and bandaged a cut before he fell off the boat and died.”

“I think I saw a nice girl once, at least half of her. She wore a white dress and had a swollen lamb’s heart. She jumped over a fence and disappeared into a meadow. gone in a an instant.”

Or like my brother, they’re chased away. They disappear into the swirling center of city skyscrapers, and do not come back.

#

My brother hadn’t liked school either. Told me that when he sat and tried to read, the words were frozen, but when he sat outside and watched the trees, they were warm with movement, with music, with the singing, growling, vibrating tremolo of everything in existence.

“I can’t learn anything sitting inside all day,” he said to me once.” You wouldn’t put a sheepdog in a reptile terrarium and expect it to grow cold-blooded, would you?”

#

I started the four miles back home, just off the road so that no one driving by could see me through the trees. I’d walked that way often, following a trampled deer path. On the bus I felt trapped. I’d grown used to my brother’s idea of freedom, that anything inside of walls was suffocating, that there should always be a way to escape.

The uneasiness crept up into my stomach first.

Like I’d eaten something rotten, so that it spread cold through my intestines.

Then it was in my head, like crawling, living dirt.

Soon it got into my fingers. My feet.

The wind picked up. And with it, this gentle, almost wooden clacking.

A sound that I couldn’t remember hearing before. A sound that ruptured through my head in much the same way a dream does.

The sound of bones.

I couldn’t look behind me. I couldn’t look, because he’d be standing there. He’d be bristling and black and angry enough to electrify my skin with a touch. He’d have teeth sharp enough to melt my eyes. He’d carry a dead rabbit in one hand and a torn child’s arm in the other, and when I glanced at his face he’d snarl and tighten his grip so that they’d both collapse in his fists.

I didn’t dare.

I walked the entire way back home, spine rigid, clutching my stomach to try to silence its crawling uneasiness.

The sound of bones didn’t stop until I stepped inside my house and closed the door.

#

My mother burst in from the garden, her skin flushed. She always looked redder in moonlight, as if it warmed her in a way the sun couldn’t. And she was smiling, lips peeled back as if she couldn’t quite remember the shape.

Like I couldn’t quite remember if her teeth were always that sharp.

“Hey Effy!” she said, and I flinched.

She headed toward the wine rack, twirling her hair, bouncing a little. She took out a bottle of wine, blew the dust off its label. A vintage Virginian Norton

“Come celebrate with me!”

I sat at the table, unable to feel my legs underneath me. My body ached from the pressure of the dogman’s eyes in between my shoulderblades.

She pushed the wine glass at me. I watched its seismic swirls.

“Won’t dad be angry?” I asked. “If we drink his wine?”

“Your father—” she paused, and then sat down.

The way she said it, ‘your father’ sounded like a bad test result.

“What are we celebrating?” I asked suddenly, and she brightened.

“I found his paw prints around the trees out back. He’s been watching me! He knows that I’ve been tending the garden for him,” she said, and then. “Why aren’t you drinking your wine?”

How quickly she could go, from buzzing and smiling, almost like a child, to a large and angry and bruised wolf.

I drank the wine. I didn't like the taste, never had. It boiled in my stomach.

"The flowers will be in full bloom soon," she said. "And then I'll make his bouquet. When it gets winter, he can come out of the trees, and I'll keep him warm."

My mother went up to her room, and I headed toward the trees with a pen flashlight. I walked on wobbly legs, drunk on an empty stomach. I felt warm in all the wrong places. My blood like heated sugar. My head like a freezer burn. I heard it right before I got to the treeline. The sound of bones.

I didn't want to be out there, searching for him in the dark. I didn't want to kneel with the pen flashlight pointed at the ground, the bones squeezing in on me, the thought of his breath swirling and heavy in my hair.

Everyone knew the dogman wasn't real.

He wasn't real.

A frantic tremor pushed through my shoulders. I spider crawled onto my wrist. I flicked it away. I must've been out there for over an hour, scanning the ground with that tiny light.

I couldn't find any pawprints.

But I still couldn't breathe.

#

In my dreams I fed translucent ants colored sugar, so that they became a rainbow as they passed between my bare feet. Green. Orange. Blue.

But then, the ants stopped coming. They left a space in their head-to-tail marching, so that the ground lay empty.

When the ants came marching back, they were bright red.

I followed the trail of red on my hands and knees. The wet, red dirt stained my fingertips.

I touched a quivering pile of meat.

A dog, laying on its side, its insides strewn in the dirt and covered in ants.

The dogman’s great paws seized me by the hair, and he hauled me to my feet. He pressed my face close to his so that the saliva that dragged from the top of his teeth pooled into the cusp of my lip.

When he spoke he did not speak with his dog mouth. He spoke with the forest. He spoke with the trees, and the blood on my hands, growing into the shape of words.

“I have never met someone with eyes that do not belong in their face.”

Then his claws were at my cheek. At the top of my shirt. He tore the buttons from the cloth. Not in the clumsy way that dogs but, but in the way of a person who’s trying to get to the skin underneath.

After he undressed me he lay me down on a slab of petrified wood, crusted black, cold against my spine that was now ticking like a clock.

I met his eyes. They were more violent than his teeth.

His claw pierced my belly button, pulled upward, dragging with it a straight line of blood. He gripped my thighs. His fur rubbed against the insides of my legs.

“And you have the eyes of a muddy pool,” he said. “trying to be a human being.”

I awoke. Not in the woods, on a slab of petrified wood, as I first thought. But in my room. The drying clothes hanging against the bedroom closet lifted up with the draft. I squeaked, and then quickly swallowed it. If he’d been watching me then, from the corner or the window of the room, lips peeled back, an almost-human smile, I wouldn’t have made any sound at all.

#

I haven’t been able to think much of my brother lately. I wondered what he’d say about the dreaming dogman undressing me, pressing his bloodied fur against my skin. But that’s not a dream I could tell my brother.

Evangeline would have said, “You should really stop watching so many fucked up videos on the Internet.”

My father would say with a soft, amused voice, “You’re becoming just like your mother. And here I thought maybe you had a future.”

My mother would say nothing. Not at first. She’d try to smile, but it’d be as difficult for her as breaking a bone. Her eyes would fade of any warmth, shutting off the lights. She’d leave the room, and only emerge later that night. In my bedroom door. A ghost of a woman, her body gone to make more room for her shadow.

“How could you?” she’d say quiet. “You knew he was mine.”

#

My brother was always giving me objects to protect myself. Not only the bone necklace, but a lock to put on my backpack. A can of pepper spray. He gave me a hunting knife when a feral dog bit me. The switchblade came when my mother hit me again, hard enough to draw blood.

You have to be careful to hide things when you live with a wolf. She had a tendency to creep into my room, to rummage through the drawers, my closet, try to pry open the floorboards, but I hid the switchblade well.

She never found it, but she knew anyway, somehow. She must’ve felt the heat leave my body when she screamed and I pressed my hand against the switchblade in my pocket. The way my brother and I stood on the porch in the morning before school without speaking. He drank black coffee and I drank orange juice, leaning against balustrades opposite of each other. We carried our new secret like a tense rope between us.

The thing we spoke about without speaking:

Some people are born in warm dens with pink walls and soft edges so that they are not hurt when they fall.

Other people are pulled out of that den, dropped onto cement and sand, so that their skin is rubbed off at the elbows and knees.

We don’t have to say which ones we are, and why we need to protect our bodies that have been rubbed raw to the bone. Why we need to prepare ourselves.

I awoke one night shortly afterward to the sound of my mother screaming herself hoarse.

“I can’t even feel safe in my own home, with you two always conspiring against me!”

She pushed my brother through the open front door, so hard that he fell and cracked his head against the steps.

I expected him to fight back. To say to me, as I stood at the top of the stairs, “I’m going to save you.” As he stood up, shaking, his hand moved to the jacket pocket where he kept his knife. Maybe it was because he was too sick and dizzy with vertigo, pain shooting through his eyes. Maybe it was because my mother, sick-skinny in her nightgown, seemed more pathetic than dangerous.

Maybe because he wasn’t yet ready to kill, despite everything.

He did not pull the knife out. His eyes softened, like he was releasing a deep and toxic strength.

Then he got in his truck and left.

#

She harvested the flowers to make the dogman’s bouquet. A wilted and sick arrangement of flowers. She cooed over it at the kitchen table as she cut the stems, ran her fingers over the petals as if they were made of silk. It took her hours, and when she was finished she tied up the bouquet in a velvet bow.

Maybe she dreamed of the dogman too, splitting her on top of a piece of petrified wood. The nightgown torn in half. Her red hair in his big fists.

“Tonight’s the night,” she said. “Come curl my hair.”

So I followed her to the vanity. Shaking and stiff, I unwound the cord for the curler and plugged it in. She dressed in her pink nightgown. She applied red lipstick so old that it pressed onto her lips in dried flakes. She caked dark eyeshadow onto her lids. The eyeliner, She tipped the eyeliner like blades.

“I know it’ll be difficult having a stepfather,” she said as I set the curler to her hair. “But we’ll get through this together.”

When we were finished she made a motion as if to kiss me on the forehead. I jerked backwards, hitting my head against a coat rack.

Usually she would be angry when I did not humor her sudden, spontaneous impulses of tenderness. This time, she left without speaking.

With her sick bouquet in its big black velvet bow. Toward the treeline.

#

I went to my room. The cold draft of the open window hit me like a bad stranger. I had no memory of opening the window, but I must have. My mother was too busy preparing for her meeting with the dogman to pry apart my room, and my father wouldn’t have.

I reached for the bone necklace in my pocket.

It wasn’t there.

The rush of panic hit me right in my stomach. I grabbed the corner of the wall as if to keep myself from falling. But sooner than I expected, the panic dissipated.

It was not the human part of me that crept to my bed, peeled back the coverlet, and smelled the sheets for signs of him. That ran her fingers along the edge of the open window frame, searching for tufts of fur, for blood, for anything that would belong to him.

It was not the human part of me that took the switchblade from its hiding spot. That pulled on my brother’s old hunting jacket and slung his quiver and bow across my shoulder.

That needed to find him.

Like I’ve said, it’s easy to lose. Easier than anyone might think.

As I walked down the stairs, my father stepped outside of his study.

“Effy?” he said, in a way that he hadn’t said my name in years.

He clenched a pen in the side of his mouth, and held a jar of dead spiders in one hand.

“Have you seen your mother?”

I shook my head. His eyes fell on my bow.

“Going out?”

I must’ve responded somehow. But I couldn’t remember, because all I could see was what’d happened to his face. It must’ve fallen off years ago. I saw that he’d taken that face, dried it out in alcohol, then pinned it back onto his skull. Just like he did with his spiders.

He did not call for me when I ran out the door.

#

I searched the trees for a sign of for my mother, for a scrap of cloth or a wilted flower, but there was nothing.

#

I tried to call for her, but the sound became trapped in my throat.

The forest was big and open and quiet.

A hungry child, who cannot ask for food except by opening its mouth.

This was my last chance, I thought. To tell myself, “he isn’t real. Everyone knows the dogman isn’t real.” To turn back.

But when I looked behind me I only saw the sad house, the broken garden, the broken wrist, the girls with stardust eyes who’d torn my skin off, the father who walked around inside of a dried out human suit.

I kept going.

I hadn’t gone into the forest since the night I dreamed of the dogman tearing my shelter apart. In my absence, he’d transformed it. My familiar pathways, the deer trails, the trees I’d marked with the tip of my knife, were all rearranged. The sky was muddied, stars removed, like water mixed with ash. The trees were bigger than I remembered, shivering and wounded.

I tried to find some sort of grounding, some path, but soon became lost.

Then, that sound.

That dry, uncomfortable music.

The sound of bones.

I could not see the trees my brother took me to once, where the bones were tied. I could not see anything moving except the slight sway of trees, the brush of weeds. But still I heard those bones, as if they were sewn into my hair.

Then beneath that sound, I heard him.

When you cease to become human, you can not always be responsible for your actions. You do not hunt and sleep and kill because you want to, or because you’ve come to a conscious decision to act. You are put into motion by deep electrical impulses, by magnetic fields, air temperature, estrus, movement, noise, teeth.

He was behind me. Matching my movements. Stepping in with me, stepping out. I kept walking, slipping my hand into my brother’s jacket to touch the switchblade. Opened it with my thumb, just a little bit, to feel its cool edge.

And then:

“Effy?”

I didn’t recognize the voice at first. It seemed to almost be a growl, a non-word, so I was surprised when I turned and met eyes with my mother.

Her pink nightgown was shredded. Mud caked her legs up to her thighs. She carried what was left of the bouquet under the crook of one arm.

“Did you find him?” I asked.

“Did you?” she asked, taking a ragged step forward.

Silence. Even the sound of bones ceased.

She took another step forward. Her mouth open. Her eyes open wider. In the dark her teeth shone. Encrusted and sharp white.

“I can smell him on you.”

“Please stay away,” I said.

“I can see his marks on your neck,” she said, taking another step.

On impulse, I touched my neck. But I felt nothing.

“My own daughter,” she whispered, trailing broken flowers.

I stepped backwards and slipped out of sight behind the foliage.

“I should’ve known, all those days out in the forest. You were running to him,” she said.

I walked slow, so as to try to not make noise. Backwards, so that I could see her walking toward me through the leaves.

“It’s your father’s fault,” she said. “That hot blood of his. I should’ve recognized that look in your eyes. I’ve seen that look plenty of enough times.”

I came to my shelter. Buried in the dark, blended into the coating of trees, difficult to see unless you knew where to look. I knelt, slow.

“Effy,” she said. “We have to be honest with each other. You have to be honest with me and tell me how you did him.”

I held my breath and crawled in backwards. I lowered my body into the dirt and waited.

She began to scream. Heaving, upended howls that could’ve been my name, that could’ve been a bat sewn into a human skin, shrieking. She paced around, searching for me. She tore between the trees. Her screams had the consistency of a nightmare, stretched so thin and so far, storm-ready, liquid heavy. I imagined my thin, sickly mother upending the trees. Killing the animals. Anything was possible with a voice like that.

When she stopped screaming, it was only to inhale in a ragged gasp so she could scream some more.

My heartbeat slowed to its normal pace when I pulled out and opened the switchblade. I clasped it between my hands, rested on my chest.

Then she stopped at my shelter, her muddied bare feet next to my head. The air swallowed what was left of her screams. She panted.

“Effy.”

She kicked the side of the shelter, smashing the branches. She grabbed me by the hair and hauled me upwards. I did not see her face. I only saw an empty space filled with sharp teeth.

“You knew he belonged to me,” she said.

She pulled her fist back, as if to punch me across the head.

It was not the human part of me that spoke, quiet and vicious:

“He’s mine.”

I slipped the switchblade through her ribs, into her heart.

I would not look at her face, as she slipped into a cold spasm. Her pink nightgown caught in my mouth. Her fist, uncurling against the top of my head. I stepped back, and the knife that I pulled out of her was more blood than steel.

I would not catch her as she fell. I would not touch her as she lay still.

In all the different ways and permutations and methods in which I imagined over the years I’d have to kill her, I did not catch her.

What I did not imagine was how small my lungs would feel afterward, unable to take in quite enough air.

#

I imagined my family standing around the body of my mother. My brother, in his blood orange hunting jacket. My father, in his stiff button-down. My brother kept snuff in the pocket of his cheek, but he wouldn’t chew. A preserved spider sat on my father’s shoulder, its body red like a devil.

“Are you going to help me with this?” I’d ask, looking down at my mother’s body.

My father laughed. My brother put his hands into his pockets and looked away.

We were not a family who were born of cathedrals and saplings. We were not the Evangeline’s and Terra’s and Lily’s of the world, who fit neatly into their human houses, their human bodies. We were animals that’d crawled out of the mud, stitched for ourselves skins with human fingerprints, walked amongst real people, ate their food, laughed at their jokes.

But our eyes would always give us away. There would always be that inevitable moment, when we could no longer pretend we were like everyone else.

I dragged my mother deeper into the woods, inch by inch.

#

When the dogman walked through the trees, he did so in heavy, arthritic steps.

He looked nothing like he did in my dreams.

He was maybe six feet tall, with worn-out, stained fur. His face was tired, his blue eyes perforated with cataracts. His muzzle was scratched and scarred.

He coughed, and his ribs heaved.

He was not followed by the sound of bones, by thunderstorms, by the smell of blood.

Only a scent like dust, and dandelion.

As he moved toward me, the air was quiet, except for the punctured sound of me trying to breathe.

He stopped in front of my mother’s body. He tilted his head to one side, questioning. His body swayed slightly from side to side.

Again, I reached into my pocket for the bone necklace. Forgetting that it’d been lost.

I expected to panic when I felt nothing there, but my body was calm and dry and dense, like the forest.

I no longer recognized my own smell.

He reached for me with a paw. His dirty, aged paw with the claws worn down almost to the nerves.

I didn’t flinch, but my body went rigid.

He plucked a dead flower from my hair. One of the flowers from my mother’s bouquet, a dead brown wildflower with a scrap of velvet bow still on its stem.

He brought the flower to his nostrils. Sniffed. Then pulled it back to regard it, turning it around to look at from different angles.

“It was for you,” I said.

Perhaps I only imagined that he smiled, the lines of his snout upturned.

He glanced back down at my mother’s body. She was unrecognizable to me now, without her hard lines, the way she snapped when she walked, the way she seemed to make everything she touched cold. Just a body now, its limbs softened. No cruelty left.

“I had to,” I said.

He tucked the flower behind his ear. He bent down. Picked up my mother.

He cradled her to his chest, her blood dark against his fur. He smoothed out her wild red hair.

He looked so small holding her.

The dogman glanced at me once more before walking off with her body. Whether his eyes were empty of reflection or there was nothing for him to see anymore, I couldn’t be sure.

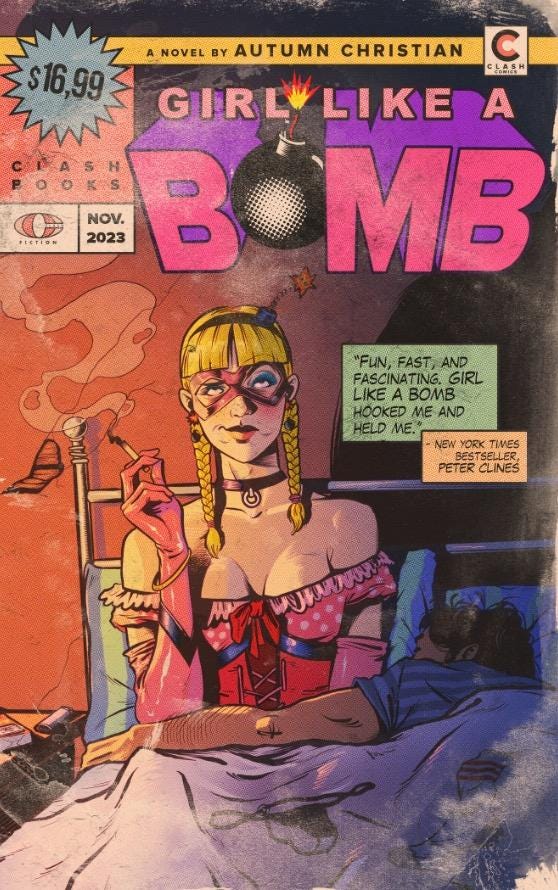

The second edition of Girl Like A Bomb is now available for pre-order! Grab it either on Amazon or on the CLASH website.

Violets and violence.