How The Sims Gave Me My First Existential Crisis

The truth of existence inside The Sims sandbox.

“Also, after people play these Sim games, it tends to change their perception of the world around them, so they see their city, house or family in a slightly different way after playing.” — Will Wright, Creator of The Sims

“It is good,” he thought “to taste for yourself everything you need to know. That worldly pleasures and wealth are not good things, I learned even as a child. I knew it for a long time, but only now have I experienced it. And now I know it, I know it not only because I remember hearing it, but with my eyes, with my heart, with my stomach. And it is good for me to know it!”

― Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha

Note: This is a repost from an older newsletter back when I had MailChimp and no archive, so I’m publishing it again for posterity.

Being famous and wealthy usually doesn’t make people happy. Children with starry-eyed dreams become depressed starlets and overdose queens. Power couples divorce after a few years of being at each other’s throats in their mansion by the beach. Kanye pissed on his golden globe award after a manic episode. And many of us have reached a goal in life only to realize that obtaining it doesn’t make life any less painful or confusing. The job we desperately wanted has internal issues that actually made working it miserable. The girl of our dreams turned out to have an addictive personality and a bad childhood. Or maybe we realize that the girl of our dreams just bores us, and isn’t actually who we wanted at all. Nothing we want is ever quite what we imagined it to be. Sometimes it takes years of struggling and pain for people to realize this.

I learned this by playing The Sims.

The Sims came out in 2000, and for those who weren’t around then — it was a revolutionary game for its time and became one of the top bestselling PC games of all time. The concept was simple: You have a family of simulated people, or “sims” living together in a house. They go about ordinary lives, get jobs, get married, have children, and fulfill their basic needs such as hunger and hygiene. There were no objectives and no end game, so you were free to play however you wanted. Nothing like it had ever been created before and people were amazed at how fun it could be to just play a facsimile of ordinary life. I remembered at ten years old playing it at my dad’s office, and his co-workers laughing behind me because I’d put a hot tub in the middle of my living room and a toilet on the side of the house outside.

The sims was partially responsible for jump-starting my game career. I put thousands of hours into The Sims, and the first job I ever did QA for was for The Sims 3: Pets for console. My first game design job was for TheVille, which was a sort of sims rip-off for Facebook. And I’ve recently started playing Sims 4, after holding off on purchasing the game for six years because I was in a losing battle with EA Origins.

So what does this have to do with existential despair?

Playing the Sims 4 has brought me back to the moments I played the first game. It came out when I was only ten years old. I’m not wealthy or famous, but my Sims were. I took them from rag-to-riches, moved them from trailer homes to mansions. And after being riveted for hours with the journey I’d have my sims at the top of their careers, with their beautiful spouse and bevy of children. They’d sit on their golden toilets, with their moods constantly in the green.

And I’d be bored.

So I’d get creative and lock the sims in rooms and make them my prisoners. Force them to sleep on the floor or piss themselves. Sometimes I’d have my sims seduce married men to get all their money, then drown them in the pool. The ghosts of all the wronged men would haunt my sim’s home, eventually driving my sim mad. Other times I’d put curtains on top of fireplaces in every room and burn my hard-earned mansions down, force my sims to wear rags and clean up the ashes and start from scratch.

If I got bored with The Sims, and The Sims was supposed to be a representation of real life, then what did life have to offer to keep me from being bored? And now that I knew getting to the top of my career, having children, and getting all the money I could want didn’t radically change my understanding of life — then what the hell was I supposed to do?

Was I too, just caught in a simulated loop, a person on a save file pulled out only to be discarded a few hours later? (I mean, probably not, but it’s fun to think about.)

I wrote this story about the Sims back when I was 18 and I’ve unearthed it from the vault of my email account for your reading pleasure. Fair warning, I was a serious edgelord back when I was 18 years old, and some of the references may be confusing if you’re not actually familiar with the game.

Autumn Christian Arrived in SimCity…

I should have known something was wrong from the beginning when Autumn Christian arrived in SimCity. Fresh out of college, I assumed, twenty-something with mechanical motions and a perfect expressionless face, studious, myopic, an ambitious bachelorette. She had college loans to pay, so all she could afford was a small white trailer on the edge of SimCity, with a patio and a grill attached to the back, a toilet and sink that was constantly being broken, a refrigerator that probably once housed the cool broken bodies leftover from some methodical machinations.

Autumn Christian the sim was alone but not lonely. She filled her small trailer with objects to keep her mind occupied and skills honed. She took a job in the medical career but soon found the hours too demanding. After a few promotions she quit and got into the science career. She kept a laboratory in her bedroom. She read books on every subject she could find. The trailer made noise in the night, and there were frequent burglaries, but Autumn Christian was making a small salary and buying more furniture and objects to keep her interested — she was fascinated with glass, with archaic books, with chess, with her makeshift fitness center, with her laboratory and the strange potions she concocted at all hours of the night. There was something out there in the dark, but she was a bubble contained, a single-minded machine.

Soon Autumn Christian got to a point in her career where she had to network — she called up people on the phone and invited them over to have dinner and watch TV. She made friends, but she only called them up to ask for favors or use them to lift her slowly dragging social meter. She advanced in the science career. She was making more money, and the bonuses from her promotions allowed her to throw out all her old furniture and get more comfortable chairs and couches. She bought a hot tub for the patio. Her friends liked the hot tub, and were coming around more often to chat and soak in the patio after clogging her toilet and eating all her food. Even though she had less time to herself, these friends were still on the periphery of her main goals. She still studied in the long hours of the night, and since she felt off somehow like she was missing something that everyone else had, a skill or a knack, she practiced talking in the medicine cabinet mirror above her sink in the bathroom. She stretched her mouth and made faces and gestured with her hands, but Autumn Christian felt a loneliness she could not describe in her conversations with the mirror. She felt as if she could not reach out and touch the real world, that everything she experienced, every person she encountered, was like this cold, cool reflection, was nothing but an expression on the back of her brain.

Yet Autumn Christian was advancing. With her hard work and networking, she made it to the top of the career path. She felt she should be satisfied, making it to the peak of advancement, but she felt something was missing, something pivotal. She drew up blueprint plans to demolish her trailer and erect a nice, modern house with all the state of the art amenities. She threw herself into this project, but once the house was erected she wandered the halls in the night, reading old books she had already memorized, working out, cooking and taking showers, fixing the shower when it broke. When the expansion pack came out, she bought a dog, and she trained it and fed it and played fetch, but the emptiness wouldn’t leave her alone.

She decided she wanted to fall in love. She called up one of her good friends, fed him, took him out to the hot tub, hug hug talk hug hugged, kissed, kissed again, kissed again until the pink heart turned red. The next day after the same routine, she, being a forward-thinking feminist science woman, proposed to him. He accepted and they got married. He moved into her house. The dog didn’t like him at first, but he made friends with the dog. They got another dog. They made love, whatever parody of love they could anyways, with the blur on everything. Autumn Christian was content. For a while.

The husband wanted to have kids. They had kids. One. Two. Three. Four. She knocked down walls of her house and added new wings, special bedrooms for all the kids, and a playroom, and a garden for them to run and play in. Even then, sometimes her husband would come across Autumn Christian in the garden, playing chess with herself, muttering, reading the books she’d read a hundred times over, pacing, making dinner that she didn’t eat, yelling at the kids. When her husband asked what was wrong she couldn’t tell him. She didn’t know how to tell him, so she burst into tears. She couldn’t tell him that she felt as if there was this pivotal center inside of her, a mechanism for the entire world to turn around, and all of this, the dogs, the kids, the house, even her husband, were just pieces, slots to be fit, necessary things that everyone told her she needed to have her whole life but that she never really wanted. She’d just been taught to want these things, taught that these things would make her happy. But they didn’t.

Another expansion pack. They went downtown and caroused the bars. They went on vacation. The kids never left her alone. They wouldn’t just grow up and get out of the house. She couldn’t even remember their names. They all looked the same, the same rote, expressionless faces, the same high-pitched, indistinct voices. One day, while the kids were at school and the husband at work, another expansion pack came out. A strange man came to her house and left a package on her doorstep. This is makin’ magic! he said. She took the package and went inside. She built a special room and put together all the equipment. She became a magician. She snorted the magic. She sold the magic to her friends. She was addicted. She knew she was addicted, but the world went away, it dissolved through her fingers. At least, for a while. She was so absence, always makin’ magic in her secret room, that all the kids got sent to military school and the dogs taken up by animal protection services. She and her husband got into vicious fights, and he went around the house, throwing tantrums and sulking. One of the neighbors eventually saw Autumn Christian makin’ magic and reported her to the authorities. She decided to get help. She threw away all her equipment, broke her wand, made up with her husband, had four more kids, bought two more dogs. She tore down the special room. She had lost her job, but she got a new one and quickly got back up to the top.

The emptiness set in just as quickly. It knotted in her stomach. These people, this house, Autumn Christian knew they were all illusions constructed by her head. They were illusions that she would never be able to touch. She threw herself back into her work, but this time, drawing up blueprints for her house, secret rooms, staircases to nowhere, elaborate mezzanines with fifteen computers and six statues of David, rooms with windows that burst the sun, rooms with no windows, trapdoors, rooms within rooms, a hedge maze half a mile long that visitors had to navigate through trying to get to her front door.

Her husband tried as best as he could to navigate through the labyrinth that Autumn Christian constructed, but it was becoming unbearable for him. This wasn’t his labyrinth, after all, it was hers, it was the windows and passageways and doors and staircases she saw in her head, the mazes that went down and down and down into endless tunnels, the rooms that squeezed her head, that made her feel safe and everyone else insane.

She lost her job again because she couldn’t get through the maze in time to get to her carpool. No matter, she had plenty of money saved up. She just had to sell all her appreciated artwork and the children’s beds. The children just fell over and slept on the floor when they got tired enough. There was nothing left. This was reality here, inside her head, and nothing left. She began luring strangers into her home and trapping them in hidden rooms. She watched through secret windows while they died. When her husband found out, she waited until he took one of his late-night swims in the pool and removed the stepladder. She burned his drowned and bloated corpse and put the urn on a table.

The kids were taken away. The dogs were taken away. She was alone again, just like she started, but this time the labyrinth reflected in her head had been made her external reality. The labyrinth had been there all along, even when she was in the trailer park, but now she could see it clearly. Now it was all around her, radiating outwards, forever and ever, her in the center, its sweet and unaffected minotaur, its rocking cradle, its axis. Everything but the labyrinth had been a lie she had constructed in an attempt to keep her attached to the world, but this, these mazes, these walls, these dead bodies whispering in the walls, this WAS her world. She had enough money to last her a lifetime. Nobody ever visited anymore, they couldn’t get through the hedge maze out in the front, and even if they did, Autumn Christian never answered the door anymore. She went about her normal routine, ate, slept, showered, soaked in the hot tub, read the books, talked to herself, played chess, worked out, swam in the pool, dressed in the same lacy print dress every day, dressed in the same jumper pajama suit every night, but always, continuously making plans for the labyrinth, making the world inside her with its phosphenes and fractal patterns and auras a reality.

Autumn Christian knew the life they advertised on The Sims(TM) box, the careers and family and love, was never what she wanted. It was never what anyone really wanted, only told that was what they wanted, to keep the houses orderly, the families neat and functional, the labyrinths locked in the head, the meaning put into the relationships, the reality put into the children, the emotions what the sims felt for one another, love and hate and passion and ambition, consequences that actually mattered. Autumn Christian once believed in those consequences. She lived them, but she had seen them in the end for what they really were, and discarded them. She discarded everything for the labyrinth, walked the labyrinth, whispered to the cooling bodies, spoke to death and made zombies rise from the ashes, discarded everything for the fractal dream that had been inside her head the entire time. What a perfect simulacra The Sims(TM) is, Autumn Christian thought, to teach us the utter meaninglessness of a normal life.

In the end, even the labyrinth was a lie.

Even the labyrinth could not justify her existence.

Autumn Christian built fireplaces in every room, every hallway, every secret morgue and laboratory, every fenced in garden and maze. She hung curtains over the fireplaces, set rugs next to the fireplaces, filled every empty space with dollhouses. She went about these motions as she always went about every motion, rote, calculating, mechanical, either unwilling or unable to consider any living creature except herself. She knew that she did all she could on her limited plot of land, built everything she could, constructed everything possible, bought everything possible, and still, it wasn’t enough.

She worked fast. She went from the top room in the farthest corner and worked her way down, lighting the fireplaces in every room. The rugs and curtains and dollhouses caught fire quickly. By the time she finished, the house was a big, blurring blaze. She stood in the middle of the house and watched her labyrinth burn. Watched herself burn. Autumn Christian caught fire quickly. She crumpled to the floor and died. Death walked through the maze, trailing his robe, clutching his scythe, just as he had for every person that Autumn Christian had murdered in the walls of her labyrinth.

There was no one to see her crumble.

There was no one to see the labyrinth dissolve, and there never ever really was.

Of course, real-life has more intricacies, challenges, money sinks, and random events than The Sims. Once you become rich in real life it’s not like you run out of things to buy in the catalog. And once you have a child the struggles have only begun. But many of the principles are the same.

(And wow, I was really obsessed with labyrinth imagery at that age. But I digress.)

After my existential crisis was over I realized that the point of The Sims was not to achieve an arbitrary end goal. It was to become engaged with the process of getting there.

Life happiness wasn’t about goals. It was about processes. Creating the perfect life was not just about aiming for something. It was creating enjoyable habits and structure. It’s been said many times that the goal isn’t the point, it’s the journey that matters. But sometimes we have to learn that lesson ourselves to really understand it.

But sometimes I just have to play with The Sims, kill my virtual wives, laugh with the Grim Reaper, and dance right on the razor’s edge of acceptable behavior. To question existence itself. To wonder — what if I was a serial killer portrait artist or a jealous astronaut who impregnated half the town? If God is real, would he let me murder my neighbors?

Sometimes there’s nothing more enjoyable than creating a little drama.

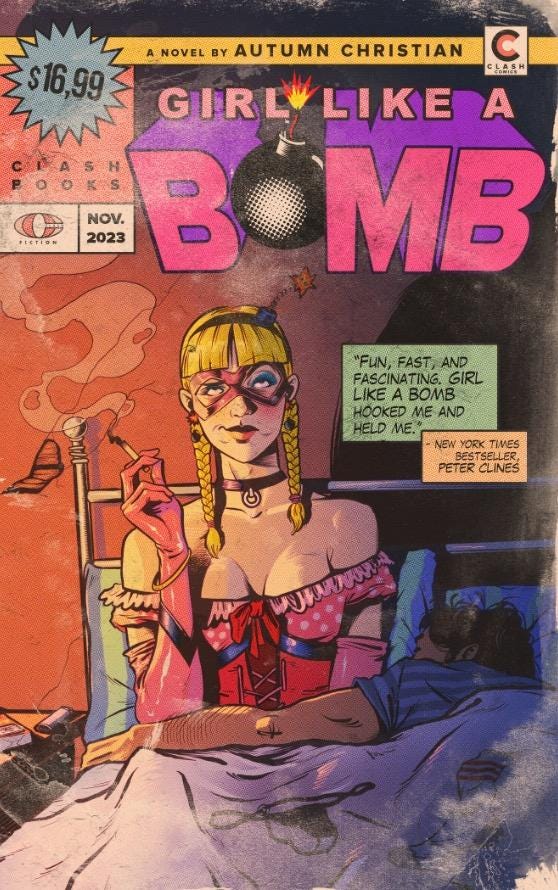

The second edition of Girl Like A Bomb is now available for pre-order! Grab it either on Amazon or on the CLASH website.