Insanity

What it really feels like to live on the edge of madness

“I am not well; I could have built the Pyramids with the energy it takes me to cling on to life and reason.” - Franz Kafka

“How can I put this? There’s a king of gap between what I think is real and what’s really real. I get this feeling like some kind of little something-or-other is there, somewhere inside me... like a burglar is in the house, hiding in a wardrobe... and it comes out every once in a while and messes up whatever order or logic I’ve established for myself. The way a magnet can make a machine go crazy.” - Haruki Murakami

How does it feel to be crazy?

It feels fucking fantastic.

You shouldn’t be fooled by the way the sick woman shudders and grimaces, her face locked into agony and hands tearing out her hair. You shouldn’t be fooled by the people who have lied to themselves, who preach that they want to recover while their tearful face is buried in a therapist’s couch. Going insane is one of the greatest pleasures in life.

I always knew that something was wrong with me. I was unable to articulate it. I was just a child. When my mom dropped me off at preschool, there seemed to be an invisible wall between me and everywhere else. I looked across the chasm with longing and wondered why I couldn’t be like the other kids. I couldn’t even explain what being like other kids would look like. But I wasn’t like them. And they knew it too. They could see it in the way I’d become like a fearful animal, bug-eyed and shy, and mostly stayed away from me.

They probably wouldn’t have been able to articulate why they stayed away either, but the part of them that was instinctual, that knew how to preserve itself, understood that a damaged thing was often dangerous.

When I got older this sense of wrongness only intensified. I tried to find words to explain it, although none of them quite seemed to fit: Crazy. Bad. Social Anxiety. PTSD. Otherkin. Highly sensitive child. Indigo child? Possessed by demons? Child of divorce? I’d go to therapists who’d tell me I stored trauma in my body, and had me do breathing exercises, find the hurt in my central nervous system. I stopped eating, so then I went to psychologists who cooed about how beautiful I was while urging me to gain weight. I was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome at one point. I was prescribed soft yellow pills and went to inpatient therapy had to listen in silence while a girl talked about how she tried to commit suicide because she spent too much money on a shopping spree. A pastor prayed over me until I collapsed to the floor, sobbing, wrestling with an inarticulate dread. I felt abandoned by God.

A hypnotist tried to regress me back into a child so I could get rid of the source of my hurt. She asked me to tell her what I saw, but no images came up. I got embarrassed and made something up because I thought being unable to be properly hypnotized was another sign of my brokenness.

There was no source. There was no inciting incident. I wish it could’ve been as easy as finding one unpleasant memory at the origin, and excising it. But whenever I tried to zoom in on a moment all I saw was black static. My sense of wrongness was so intertwined with my being that it’d infected every part of me. There would be no going back to normal, because normal had never existed for me. I was a scraped-together, barely there composite of maladjustments.

I told people I wanted to be healthy, but I didn’t understand what that meant. I didn’t even know if my head was pointed toward the sky or at the dirt. I’d gotten so twisted over the years that I’d probably bite my own neck and be unable to recognize the source. What was healthy? What was normal and good? Maybe I’d seen it in a painting once above a fireplace; a mother in a sun hat with her daughter, sitting in a garden in the warmth. It was so far away it might as well have been heaven, and I knew that a person couldn’t get to heaven by going to doctors and swallowing pills and reciting positive affirmations.

I couldn’t admit the truth even to myself.

I was damned and I was damned again and I liked the feeling of being damned and if someone had offered me salvation, shining and bright in their open palms, I would’ve recoiled like it was poison.

Saltwater is poisonous to the freshwater fish. Happiness is poison to the person who has swam so far away from themselves that it’s no longer recognizable.

I couldn’t be a healthy person, and I couldn’t be good, but I didn’t have to just be a pathetic failure. I could transform into mythology. I could be iconic. My suffering could be a symbol. I’d be like Sylvia or Ophelia or Zelda. If I couldn’t get to heaven by ordinary means, I’d become so bad and so wretched that my inevitable suicide would blow open the back gates.

I wanted to be crazy.

Two years ago I went to a diagnostic clinic and was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. I’d suspected I had it for a while, but all of my therapists dismissed the possibility. “People with borderline have crazy eyes.” “They’re clingy and inappropriate.” “You’re just suffering from trauma.” Maybe that was a testament to how well I’d gotten at pretending to be normal. My therapists seemed almost aghast at the thought I might be one of them. The really crazy ones.

Despite wanting to be crazy I didn’t end up dead or in and out of psych wards or permanently disfigured from a suicide attempt. Instead, I became a game designer and wrote five books and got married and had a daughter. Maybe that’s proof for the idea that my will wasn’t always my own: For years I walked on a narrow ledge between psychosis and sanity.

The truth was, I never had the courage to go full Ophelia. I didn’t have the fortitude to drown in my own delusions and accept obliteration. So I tried to bargain with madness. Just a little sip. A little taste. I want to nibble on the corners of insanity so that it dripped down and numbed my throat. Not enough to destroy me, but just to experience some relief.

I’d learned how to hide the worst parts of me. I could appear exceedingly sane and almost approximate a normal human being. For two decades I didn’t know I had BPD, but I found that when I got too intimate with someone I couldn’t control my emotions. If I expressed how depressed and sad I was, it pushed people away. It makes sense to want to be comforted if your dog dies, or you get fired from your job, and people usually want to comfort you. Those are appropriate reasons to feel pain.

But when you have borderline personality disorder, you are a machine that generates pain. Everything becomes an emergency. You are constantly in a crisis with an unknown origin. It’s too much for most people, even the most well meaning. Especially when that machine of pain tends to turn on those who are closest to it.

So I learned how to distance myself from other people. I learned how to pull myself away from my own center. It was exhausting, and lonely, but at least it wasn’t outwardly destructive.

Yet no matter how much better I got at appearing stable, I was a wreck inside. I was still getting into regular fights with my husband that ended with me in so much crippling emotional pain I’d be on the ground sobbing. Fights that, in retrospect, seemed to be about nothing. I’d spend days in bed under an oppressive and crushing emotion. I’d get into arguments with the other half of myself- the part that I believed to be demonic, this “false self” that would emerge every time I felt threatened or vulnerable. Sometimes I called her “Nameless.” Sometimes I called her “my underwater self.” Without warning she seemed to take over my body, and inflict me with such intense rage and hatred and fear. I’d be utterly convinced that everyone hated me, that my husband was evil, that the entire face of the earth was aligned against me. I’d lash out. I’d scream. I’d throw myself to the floor.

I needed everyone to see that I was in pain. I needed existence itself to apologize to me for causing this injustice.

Then just as quickly, this intense hatred would leave me. My perception would shift. The facade that my “underwater self” had constructed me would crumble right in front of my eyes, and I’d be left gasping and ashamed. How had I seen things so wrongly? How had I allowed myself to get so out of control?

I’d promise myself it’d never happen again.

But it always happened again.

People in borderline groups call this “splitting.” It’s supposed to be a defense mechanism, but to defend against what, I was never sure. If it protected me, it protected me by making it so that I was unable to form a coherent view of myself. The truth was always a distortion. It was like I’d hurled myself through the stained glass roof of a cathedral, and now could only perceive reality while I was being crushed underneath a pane of swirling, broken glass.

Every glance a mirror. Every moment a split moment, reflected into infinite delusions.

Borderline people are often underneath the perception that they’re innocent. I know I thought the same thing for a long time. They present an air of waif-like vulnerability, a desperate and pouting visage demanding sympathy. The person who “splits” into a raging psychopath isn’t them. Not really. That’s the other them, the uncontrollable demoniac entity, the underwater self. They cease to become complicit in their destruction.

It’s a perfect way to become your own victim. You forget that you’re the monster gripping your throat. You’ve split your own tongue in half and become unaware that everything you speak is now a deviled lie. You scream in terror at the sight of your own hands gripping the bed sheets in the dark.

You can actually convince yourself that you don’t want to be savaged by the worst version of you.

I didn’t know when I was a child that I was making the decision to split my psyche. I made the decision probably before I even properly understood language, before I even could form coherent memories. I decided that I needed a protector, and that the protector needed to also protect my mind from the horrors it’d inflict on others. My underwater self carried me through my childhood and into adulthood with its bloodied back a shield

It protected me, but at a cost so expensive I never would have agreed if I’d known. And how could I have known? I didn’t even know I was making the deal in the first place. I cowered under my own gaze.

Oh, and how I raged whenever my husband told me that it had always been my decision. I’d spit venom down the front of my shirt. How dare you. I’m not evil. I’d scream at the betrayal. I’d slam my fists against the ground like I could bend the shape of matter. I needed the universe to acquiesce to my false conception of self. I did want to become better, I told myself. I did. Couldn’t he see how hard I worked? Years of therapy and self-help books and self-flagellation and exercise and meditation and pain and pain and pain.

And yes, I saw incremental improvements. I learned new coping mechanisms. I went on long “health walks.” I stopped being so volatile and maintained stable relationships. I became more resilient in the face of my pain generating machine.

I worked so hard, and yet somehow I found myself retreating, over and over again, into every available dark room.

And no matter how hard I worked to get better, she was always there. She oozed between my bones. She sucked on my brain stem. She was ready to take over whenever I needed her. Whenever I felt threatened, or felt the sting of betrayal, she would rear up, ready to protect me so I could retreat back into the tender joy of helplessness.

And if there was nothing that I needed protecting from? No problem! She’d make something up. There were demonic faces everywhere, if you were crazy enough to see them.

Once I told her, I don’t need you. It’s okay. It’s time to die. I got so sick I vomited.

I still didn’t realize that she was me.

Many people misunderstand borderline personality disorder. Most of all, those who have it. It is by design, meant to be misunderstood. Most people just equivocate BPD with crazy. Everyone seems to have some story about a BPD mother or an ex. They say that people with BPD are hot anorexics, or desperate for approval, or have wide bug eyes that are always peering into some non-existent reality. They say borderlines will destroy your life, that they can never be trusted, that they’re psychopaths. (True enough that it bears warning. Many with borderline are also comorbid with histrionic personality disorder narcissism.) They’ll say that borderlines will love you more than anyone else, that they’re intense and passionate, highly sensitive. They say the clinginess is worth the sex.

The truth is that borderline can manifest much differently in different people, but the core is always the same.

The borderline has betrayed herself by making an unholy pact with a demon that she created.

I am not a stupid woman. I’ve solved almost every problem I’ve ever encountered in my life. It comes easy to me. Whenever I set my mind to doing something, I do it. I understand the rules of reality, how to use force application, how to use error as a way to find the truth.

So I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t solve this problem.

I didn’t understand why I housed the monster of myself in my heart and kept spitting up blood in the middle of the night.

I didn’t understand why no matter how much I played in the sunlight a part of my mind was always in a darkened and cold room.

I didn’t understand why I found it painful to simply exist, like even the effort of being normal was something that was so extraordinarily excruciating that I often would simply shut down. I’d retreat from the world, attempt to retreat from myself, head in hands, back to the darkness in an attempt to touch unconsciousness because it was the only way I felt relief

I didn’t understand why no matter how many people showed me their love, I couldn’t feel it.

But I had to admit the truth to myself.

I liked being crazy.

I wanted it more than life itself.

It was the craziness that crooned and comforted me when faced with the unrelenting onslaught of the real. It was the craziness that saved me from physical illness and despair. The craziness became my god and the god of insanity loved me in a way that no man ever had. It loved me so much it was willing to sacrifice the earth to keep me safe.

You already know that a demon’s bargain is never a bargain at all. The price of getting what you want is earning hell.

I didn’t want to write this letter. I haven’t updated this newsletter in so long because something inside of me was demanding I write nothing else, but I didn’t want to. I feel ashamed of the illness I carry inside of me, and I’ve hidden it for so long. It is not something I’ve spoken of to even to many of my closest friends. I’ve never claimed to be perfect, but I’ve tried to be honest, and when the idea for this letter came to me I realized how deceptive I’d been. By hiding it, by refusing to even write about it, I was being dishonest with myself. A good writer tells the truth. I can’t pursue my mission for the truth while hiding the one thing that has affected my life more than any other.

It is shameful to admit that I don’t want to give up being borderline. But I want to want it. I know that sounds absurd, but once I truly give it up I’ll cease to exist. I’ve spent so long as two halves that I’ve never truly been whole. The woman that is Autumn without insanity has to destroy the old self. I was right when I told my other self that it could die. But really, we both had to die.

I know what it’s like to live in constant, benumbing pain. I don’t know what it’d be like to live without it. The thing I have to become is alien to me. Who would I be when I’m no longer victim and monster, innocent and terror? Who would I be without the constant self deception and sabotage, the rage and the dark?

I’d like to meet her.

I’d like to.

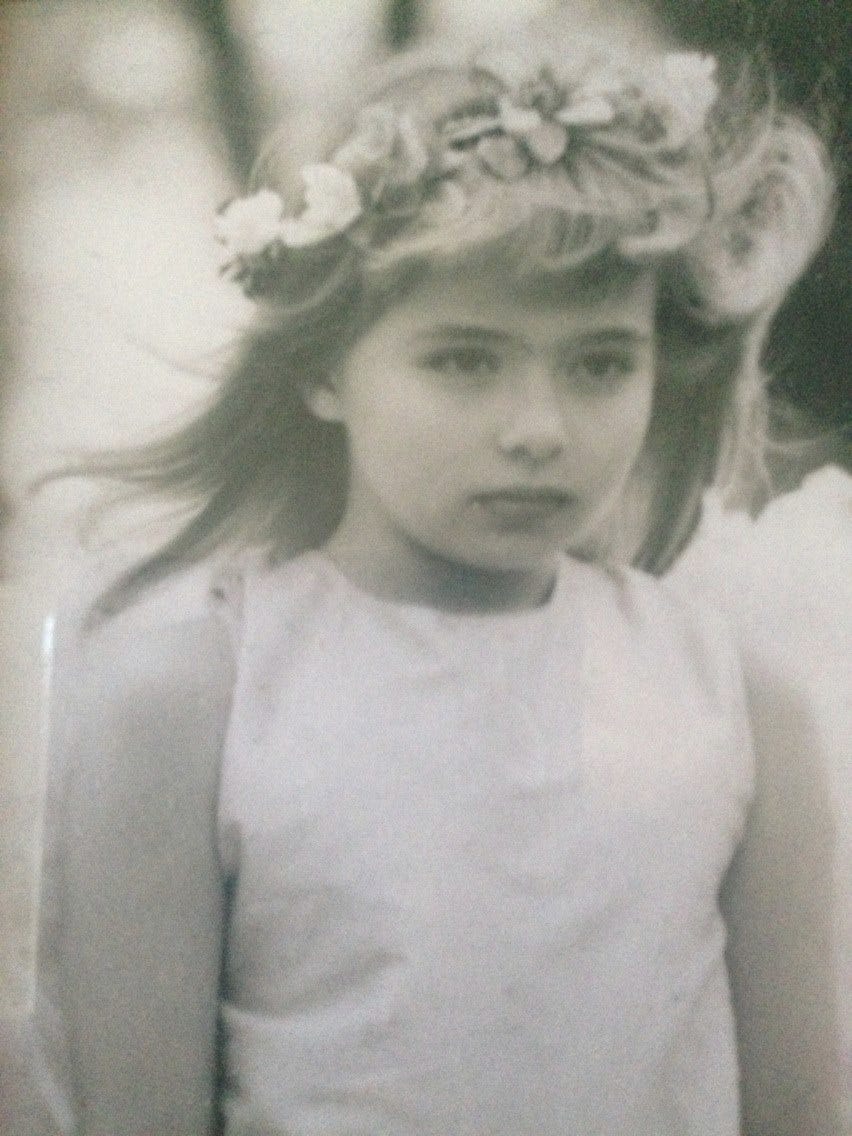

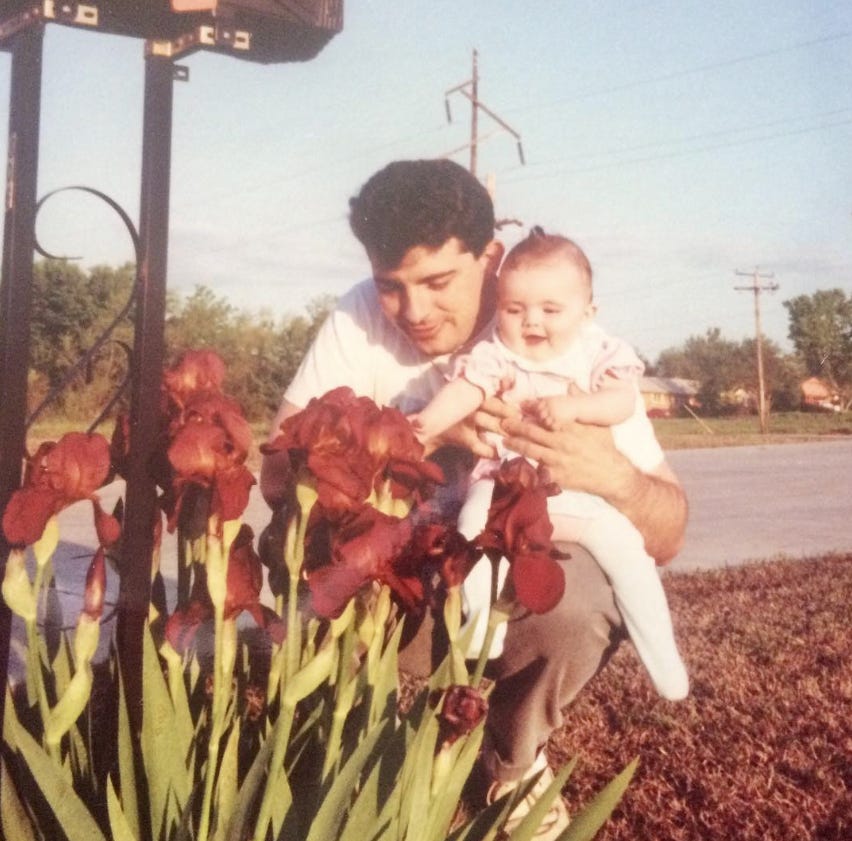

It hurts to look at pictures of myself as a child. It hurts so bad my throat clenches and I can hardly breathe. The girl in the pictures is bright and laughing and smiling. She’s golden and pretty and inquisitive and clever. The girl in the picture is completely different from the conception of myself I have of those times.

I was not a little deranged monster. I was not an oozing sore, insanity incarnate. I was a child. And despite my bad moments, I had good ones too - sometimes fractured from myself that I was unrecognizable, but they were there all the same. I was crazy, but I was good too. I was insufferable, but I was also bright. I was selfish, but I could also be empathetic and generous. The broken cathedral I lived underneath with all its split mirrors of perception often hid my goodness from myself. I could only see it sideways - in periphery, in moments when I was viewing myself as not myself. But it was there. It was real. The pictures were proof if nothing else.

Maybe it’s not so crazy to think I could be whole again. I could nurture the good parts of myself. I could merge with my underwater self, and give her permission to stop being a monster. I could. I could. Maybe it’s easier than I imagined.

Every time I read your words, I find myself on a journey. Sometimes shockingly alien, many times painfully familiar. Like a cut to the flesh or a balm to the soul. My daughter (who hasn't spoken to us in nearly two years) suffers from BPD. This has helped me understand in infinite ways. Thank you, Autumn.

Thank you for writing and sharing this beautiful essay.